Background

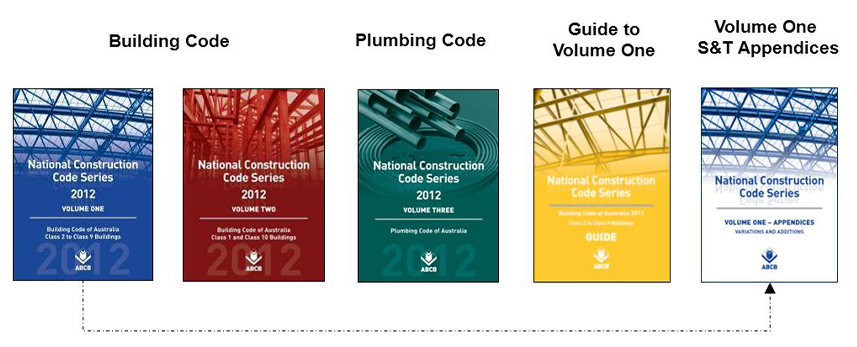

The National Construction Code of Australia (NCC) provides a uniform set of technical specifications which applies to the construction of all new buildings within Australia. The NCC consists of a suite of three interrelated volumes. The first volume focuses on multi-residential, commercial, industrial, and public buildings and structures. Residential and non-habitable buildings and structures fall within the remit of volume two. The third volume encompasses plumbing and drainage and applies to all classes of buildings that fall within the remit of volumes one and two. The three volumes are accompanied by the supplementary explanation guide.

Incorporating the technical specifications into New South Wales law

The Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) (EPA Act) is the legislative instrument designed to regulate the process of environmental planning and assessment applications within New South Wales. The EPA Act has ten defined objectives, one of which is the “promotion of the proper construction and maintenance of buildings.”[1] To facilitate its intent, the EPA Act enables the delegation of control and publication of particular documents to government agencies with subject matter expertise.[2] The power to do so is contained in section 10.13 of the EPA Act which expressly provides for the making of regulations.

In this instance, the derivative method of drafting is used to provide defined meaning to words and definitions used in the EPA Act, where the definitions are not defined within the body of the EPA Act itself. For example, section 7 of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000 (NSW) (EPA Regs) defines the term ‘Building Code of Australia’ for the purpose of EPA Act. This definition is critical as it is the relevant section which purportedly incorporates the NCC within the law of New South Wales. Further, the regulations specify the date at which the amendment or variation comes into effect, which is a function of the time when the relevant government entity publishes the variation.[3]

The third volume of the technical specifications has also been incorporated into New South Wales law. Unlike the method of incorporation referred to above, the third volume has been incorporated by express reference in the Plumbing and Draining Act 2011 (NSW) (PD Act).

The strategic direction of the Australian Building Codes Board

The Australian Building Codes Board (Board) is a multi-jurisdictional standards body which is responsible for developing and publishing technical specifications within Australia. The Board is not a traditional Commonwealth department per se and owes its existence to an intergovernmental agreement between the respective Australian States and Territories.

The Board takes its strategic direction from the Building Ministers Forum (BMF), which comprises the group of Australian Government, State and Territory Ministers with responsibility for building and construction.

Constitutionality

The Commonwealth Constitution of Australia only permits the Federal parliament to make laws in respect of certain matters.[4] It should suffice to say that the power to make laws in respect of the construction of new buildings and the residential plumbing and draining thereof has been a power traditionally solely exercised by the states and territories. The NCC overcomes this through an inter-governmental agreement by which the regulators agree to accept the NCC as the minimum mandatory national technical standard for the design and construction of buildings. Consequently, the NCC is adopted through individual government statutes as a mandatory national standard for all new building work.

Recently, the ACT Legislative Assembly deferred the adoption of the 2019 edition of the technical specifications. The decision of the ACT Legislative Assembly does not affect the application of the technical specifications within other states and territories. It follows that states and territories can maintain some control of over their respective suites of legislation.

The structural uncertainty within New South Wales construction legislation

The ‘incorporation by reference’ method of legislative drafting splices the technical specifications into the law of New South Wales. Inserting third party materials into the law would ordinarily require, as a matter of best practice, that the exact subject matter of that document be ‘readily known and available, certain and clear’.[5] The importance of clarity becomes clear when it is accepted that the target audience of the technical specifications, being persons responsible for implementing code, are construction professionals.

It is arguable that there are two key structural failings that have been introduced into EPA and PB Acts. This leads to the reasonable conclusion that the EPA and PB Acts do not presently hold the requisite degree of certainty required for laws of their kind.

The first issue is the questionable drafting method of including three separate yet interdependent dates that determine the operation of the law at any one point in time. The problem created by the inclusion of the three dates is further compounded where two of the dates are controlled by the New South Wales Legislature with the control of the third being delegated to the Board.

The second issue is that the delegated material is infected by the questionable publication practices of the Board. The questionable publication practices can be further divided into discrete sub-elements. The first sub-element concerns the issues created by the Board’s document control practices. The second sub-element concerns the Board’s decision to publish actual law alongside secondary materials that hold no legal effect.

To differentiate between successive publications, the Board simply relies upon a minor banner affixed on previous publications that denotes that the file has been archived. The term ‘archived’ is insignificant, ambiguous and it is arguable that it would not deter the reasonable end user from accessing the material, especially when the material is being accessed onsite using a handheld device. Whilst it may appear to only be a minor issue, the importance of this publication oversight cannot be underestimated as when the technical specifications are incorporated into the law, it should be plain and clear.

The Board has decided to publish a guide to the interpretation of the technical specifications upon its standard website. The Board has publicly disclaimed that the guide to the interpretation of the technical specifications has no legislative effect. The Board has published this guideline upon its website within the same location as the technical specifications. The decision to publish the guide in the manner chosen raises what can be regarded as more than a merely arguable contention that when the guide is published in this manner, it becomes in and of itself part of the suite of technical specifications and at that time might be incorporated into the legislation through the operation of section 7 of the EPA Regs. Even if this reasoning is not accepted by a court, the guide may, by virtue of the operation and placement upon the Board’s website, at or near the published technical specifications, be taken to form part of the technical specifications by the end user.

It is arguable that the lack of control that the executive currently holds over the publication of the technical specifications is a critical failing. One possible solution to address these failings is that section 7 of the EPA Regs be amended so that the regulation in and of itself is the instrument that determines the deemed date of publication for all iterations of the technical specifications. Noting that the amendment cycle is ordinarily 3 years, such a course of action does not seem unreasonable in the circumstances.

The amended amendment cycle

In 2016, the BMF directed the Board to reduce the frequency of the revision cycle for the technical specifications from annually to every three years. The alterations to the amendment cycle were designed to create positive outcomes for the greater construction industry. This was achieved by lessening the regulatory burden placed upon its end users.

All things being equal, the 2016 change to the reporting cycle would have seen the latest version of the technical specifications being adopted without reservation by all states and territories in late 2019 which would then be followed by another amendment due in 2022. Since the 2016 resolution, all things have not been equal, the inequality being two critical events that occurred within the 2016 and 2019 reporting cycles. It should be noted that the two events were of such significance to the construction industry that the BMF sought to provide additional guidance to the Board.

The first even was the English Grenfell Tower Fire disaster of 14 June 2017, and the second being the release of the Shergold Weir Report (SW Report). The SW Report is a commissioned report on the compliance and enforcement issues within the Australian building and construction industry that was made publicly available on 27 April 2018.

Following the two events, the Board advised its intentions to implement an out of cycle amendment to the technical specifications that was designed to address the egress from early childhood centres, the requirement of labelling of ACM, and matters of lessor significance.

The out of cycle amendment

On 1 July 2020, NCC 2019 Amendment 1 was adopted into the law of New South Wales. The out of cycle amendment was introduced into law as at the date of publication. By way of summary, the latest amendment incorporated two new provisions for the labelling of aluminum composite panels and the egress requirements from early childhood centres. The Board advanced the opportunity provided to it and also included minor clarifications and amendments for concessions that permit the use of timber framing for low-rise Class 2 and clarity regarding anti-ponding boards. All things being equal, the next edition of the NCC is scheduled for adoption in 2022.

[1] Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) s 1.3(h).

[2] Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment Act 2017 (NSW), (1 March 2018).

[3] Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000 s 7.

[4] Williams v Commonwealth (2012) 248 CLR 156.

[5] The Hon Sir Gerard Brennan AC, “Role of the Legal Profession in the Rule of Law”, Supreme Court, Brisbane, 31 August 2007 published on https://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/policy-agenda/international-law/rule-of-law.